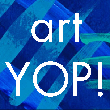

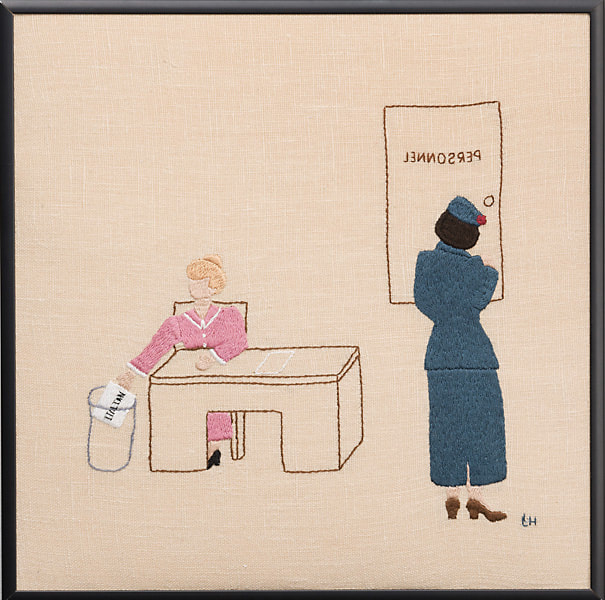

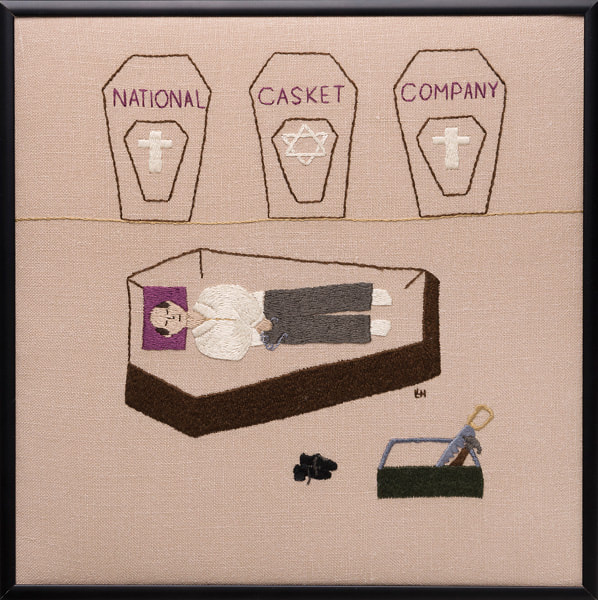

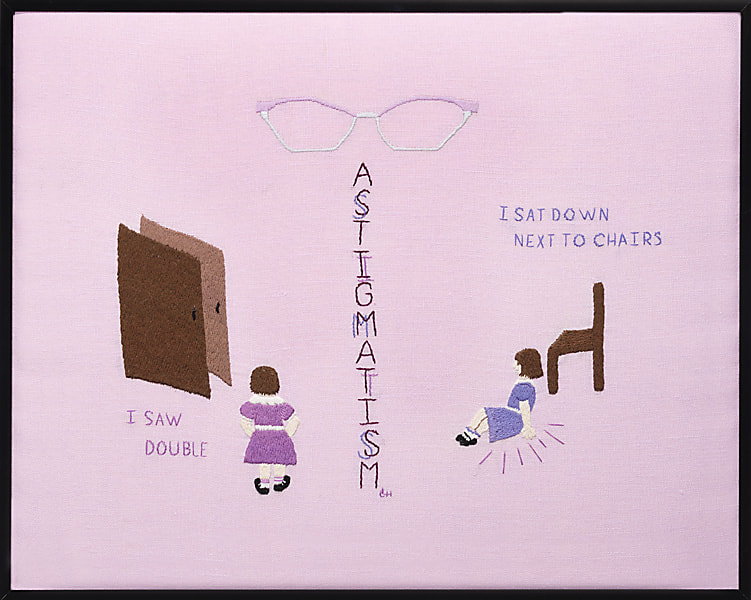

One of the first in the series was Need Not Apply: In Memory of My Mother, Josephine Schiliro LaVilla. “I decided to do this piece about my mother,” LaVilla-Havelin explained. “In the 1930s, in Rochester, New York, she went to apply for a job at the telephone company. She was dressed professionally and she thought the interview went well. As she was leaving, she turned around to ask a question and saw her application going into the trash. Because she was Italian. That’s why she always made sure we knew we were as good as anyone else.” Need Not Apply was one of two pictures from this series that were included in The Art of Labor at the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles in California in 2018. Another piece shows a man lying in a coffin—but it’s not a funeral. The Carpenter Takes a Lunch Break: In memory of my grandfather, Joseph Schiliro is an affectionate memory. “My mother’s father, Joseph, lived with us after his wife, Lucia, died (I was named for her),” LaVilla-Havelin recalled. “He worked for the National Casket Company in Rochester. Every day at lunch time he would take a little nap in the casket.” "It’s all memory,” LaVilla-Havelin said. “It’s honoring my parents who are gone and my grandfather. Seeing things that are a little odd and maybe a little spiritual.” Her Grandfather Returned as a Bird, for Anita and Ty is one of those stories. “My eldest niece was living in Oregon and had her first child, Ty. When my father was dying, she came to see him with Ty but he was already unconscious. He passed away that night, and she didn’t know if he was aware she was there. When she got home, this bird began pecking and pecking and pecking on the sliding door to the deck, and just wouldn’t stop. She picked up Ty to show him the bird, and as soon as they got to the window, the bird stopped pecking and just stared and stared. When she put the baby down, the bird started pecking again. She picked up the baby, and it stopped again. She realized, ‘That was grandpa coming to see Ty.’ She noticed a piece of paper on the deck and it was a page from the Bible that said ‘If you believe in me, I will be there.’ We’re not a religious family, at least not the younger people, but this was …!” Sometimes she herself is in the story. The Visitation, In Memory of My Father, Rocco LaVilla depicts hands on a steering wheel and a large antelope. LaVilla-Havelin said, “Jim and I were driving out to Big Bend National Park and this big antelope just stood in the street and stared at us, blocking the road. Jim said ‘Hi, Rocky’ to the antelope and it moved on. He said that was my father stopping to say hello.” (The Jim in this story is the poet Jim LaVilla-Havelin. Full disclosure: I have known the LaVilla-Havelins since the mid-1970s. Jim taught creative writing at my high school, and my sister and I attended their wedding.) “It’s weird what you remember from your childhood,” LaVilla-Havelin said, referring to the piece Me at Three. She remembers being three years old, when she would walk into doors and sit down next to chairs. “I distinctly remember seeing two doors and trying to reason out that the lighter door was not the real one, so that way I wouldn’t bash into it. Of course, I bashed into it anyway.” The word ASTIGMATISM runs down the center of the piece. “People don’t understand that embroidery can be art,” she said. Viewers are often surprised that she does all her stitching by hand, and that embroidery can be more than just a pretty decoration on a blouse or a tablecloth. To create an embroidered piece, she first draws on the fabric—linen or silk—with disappearing ink, before hand-stitching the embroidery. “Things change as I go, so there’s no difference to me than any other art form. You get inspired, you have blocks, it’s just like anything else. I just happen to love to hold it in my hand and have it be very meditative. I also like my hands to stay clean, and stitching is better for that than paint or clay. I do my thing, and if I don’t work, I go crazy.”

Looking back over her art work, LaVilla-Havelin noted, “I love color. Color is a big deal for me. I’ve done stuff that was in just blacks and grays. I did a series of bacteria at one point. It’s interesting to me how things just change. I’ve always been interested in science, in anatomy, that was a big focus of mine for several years—all those marine creatures. I never thought I could do people but then I got over the idea that they had to be drawn perfectly.” Her latest series is what she calls “odd self-portraits about things I’m going through, like brain fog.” Today, Lucia and Jim LaVilla-Havelins live in Lytle, Texas, near San Antonio. Her distinguished career has included numerous solo and group exhibition, curating exhibitions, and directing galleries. In June 2019, LaVilla-Havelin will be participating in The State of Hand Stitch, an exhibition of work by eleven women artists from Texas who hand stitch at the University of Texas–San Antonio Main Gallery, where she worked closely with colleagues to plan the exhibition. After UTSA, the exhibition will travel to the Arnold Gallery in Mason, Texas, and then to the Georgetown Art Center in Georgetown, Texas. Learn more about Lucia LaVilla-Havelin at her website. An interview with her by Linda Simone is scheduled to appear in the online magazine Nat. Brut in May 2019.

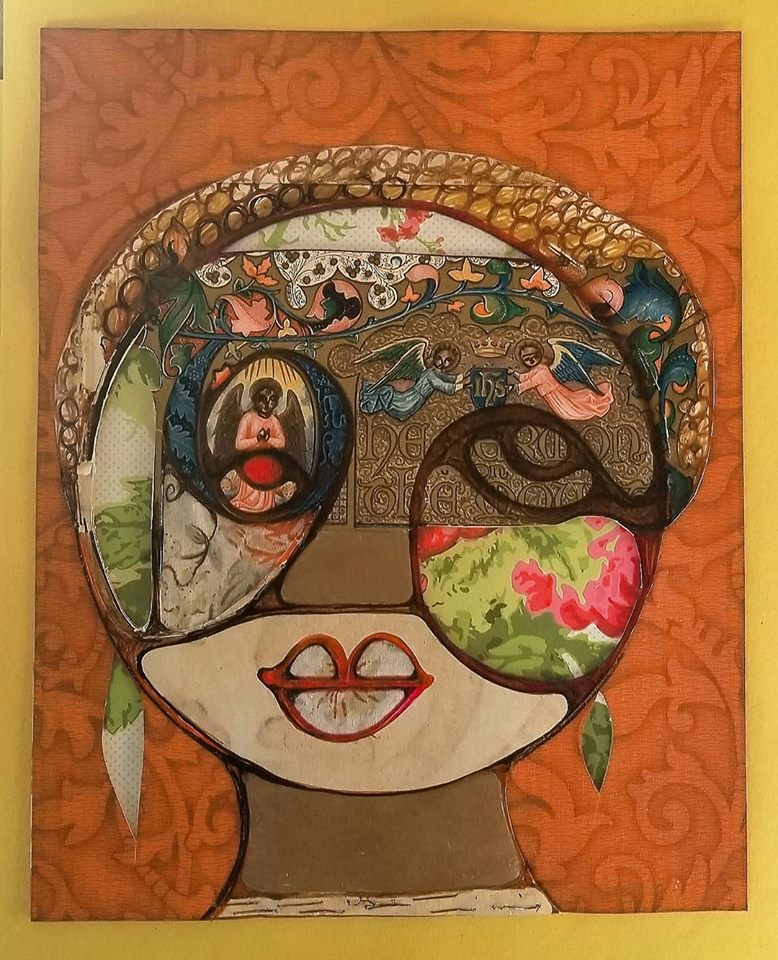

“My work has always been colorful, bright—the main subject matter has always been women, children, and family with a spiritual twist,” Kedem-DuBose says. She found it hard to create during the early years of her depression, as she had no desire to produce negative imagery. Seeking a way to take her mind off all the loss surrounding the divorce, including the absence of her youngest child, she decided to enroll in the interior design program at Harrington College of Design. She received two scholarships, one based on her art portfolio, and one as a Service and Leadership Scholar. While a student, she was invited to speak on a panel of professional Black artists, and was included on the Dean's List. “These accomplishments helped me to see that I hadn’t lost anything creatively, and also helped me to get through some of the most challenging aspects of the divorce,” she recalls. “My work became more technical, and I started to work more with the elements of design instead of the visual art foundation with which I was most familiar.” Going back to school revealed another issue that had gone unrecognized previously. “I’d forget from one week to the next what was due, so there were times when I worked for days without sleep to complete a project that I had weeks to complete.” Finally, a professor took her aside and said, “Makeba, we think you’re brilliant here, very talented, but have you ever considered being tested for ADD?” She knew he was on to something, and was subsequently tested and diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. Knowing this was helpful and she tried ADD medications, but it turned out her body did not react consistently well to them, so she learned to manage on and off with them over the years. In 2014, she met urologist Dr. Adam Murphy, cofounder of the Chicago Global Health Alliance, and began working with CGHA, first as curator of the non-profit's Annual Art for Global Health Fundraiser, then as creative director. She has been coordinating art auctions that help fund the organization’s work in the United States and Liberia ever since. She went with Dr. Murphy to call on a gallery owner she knew well, only to find her old friend in precarious health. Despite her own health problems, and being newly divorced, Kedem-DuBose began helping her friend by offering transportation, shopping, cooking and cleaning, and by consolidating the art in the gallery and selling it off. It was at this point—with practically no money and deep in depression—that Kedem-DuBose discovered what would become the first step on her journey back. She found a cache of old artist catalogs in the gallery files and felt inspired to make art out of the paper. She deconstructed the catalogs, dyed the paper pages in vats, drew on them, painted on them, put them together with pins, staples, grommets—the only things she had. The first pages were dark blue—reflections of her own “blues” as she poured all of her depression into the work over several years. Then something new started to happen. Purples. She calls purple “my best of blue—I always felt connected to the color purple, from Catholicism to Voodoo to Judaism—there’s a lot of stuff in there. Purple was spiritual and less depressing.” So the blue morphed into purple, and then she noticed that she was adding bits of a new color—red. And with red, Kedem-DuBose says, “I refound my warrior spirit.” In November 2017, the complete work, called “The Best of Blue: A Work in Progress” was displayed at Adler University’s Chicago campus. The mosaic of pages snake up and down along the wall, like the emotional ups and downs of the previous eight years. “Best of Blue was very therapeutic for me,” she says. “I was working out a lot of that stuff through art—even though I still have challenges. Some of the paintings I started back then, I’m just going back to now. My best work comes out of my depression. I’ve never been one to shy away from any subject. I’m as comfortable talking to a White person about race as a Black person. I’m the same way with my work. Sometimes I can’t restrain myself, but my intentions are always good—not just for me or for Black people, but for everyone.” Her newest work continues her interest in religious imagery, bright color, and inclusiveness, but with added layers and textures. She alters pages from old books to include people of color and women. “Sermon” is a newer work that includes the text of the Sermon on the Mount and angels repainted with African faces. “I don’t want to exclude anyone—my work is very rainbow like,” says Kedem-DuBose, “but being African American, the faces I create will always have something African about them.” She is also exploring the connections between religions, especially the Catholicism she was raised in and Ifá, which is practiced throughout the African diaspora and influences religious practices such as Vodou and Santería. “Ifá was brought to America through the slave trade,” Kedem-DuBose explains. “My enslaved African ancestors incorporated it into Catholicism. There are a lot of similarities in all religions—we’re all connected. We’d be better off to recognize that. All the major religions say the same thing. Every religion has love, but love has no religion. My religion is love. It’s a very radical viewpoint--in a world filled with ugliness, but there is still beauty.” To learn more about Makeba Kedem-DuBose, start with her Facebook page. Comments

When I moved the blog from its original site to this site, the comments didn't transfer. Here's what people responded to this post: KIMBERLY J B SMITH 3/2/2019 06:11:49 am Great journey story, enjoyed the Best of Blue as it appeared like waves across the wall. Always like to hear what is going on in Chicago!

Sheehan says that finding materials is a constant process. “I search in antique stores, thrift stores, dumps, people’s outgoing rubbish. It’s amazing what people throw away—like the glasses on the head. They were all scratched up but so simple and lovely. They’d obviously lasted someone a long time.” She used paper leftover from shredding combined with moss from her garden to create the nest. “When I find a piece, I don’t necessarily know how I’ll use it, but I know I’ll use it sometime. People throw out all kinds of things. I once found an old clock with a mahogany and brass case.” Sheehan appreciates the opportunity these odds and ends give her to combine eras. “You get something from the turn of the century or from the forties. The story they end up telling is about something totally different. Old things seem to go together in a way that newer things don’t.” Her interest in mixed media began with the rusty nails, seashells, or interesting rocks that made their way into her pockets as a child. She loved the work of Joseph Cornell and Louise Nevelson. “It made me wonder how it works. Cold adhering? Welding? Soldering? How do you make something heavy stay where you want it to be? Each piece is a problem you want to solve. It’s fun to solve those problems, one at a time, until you go that works—that’s kind of what I had in mind.” Sheehan says she tends to visualize pieces at a particular scale—some want to be large, others want to be small. Then she has to try out different objects to see what will work and become part of the piece. “What is the main focus and what counterbalances that?” Sometimes things don’t work out as planned. “If I finish a piece and think eh, I’ll let it sit for a while and then I’ll end up cannibalizing it for something else. If it sits around too long, it’s fair game. If it doesn’t work, you pull it apart. You still have all those parts to use in something else. And you learn something with every piece. Comments

When I moved the blog from its original site to this site, the comments didn't transfer. Here's what people responded to this post: SUSAN WE 2/8/2019 02:35:52 pm I loved Cilla's story about how she gathers stuff and puts them together and then reuses things if she does not like the first product. She has a great imagination for seeing many everyday objects (especially from people's trash) that put together will produce an imaginative statement which catches the on looker up into a new awareness of and issue or the shapes of ordinary things working together in completely creative and unexpected ways. Se has a great eye for seeing the stuff of everyday life put to entirely new uses. She makes the viewer laugh and delight and admire her things all at the same time.

My set is maternal—I am thinking about family matriarchies, the realm of power in women's lives, how women wield power and the bonds between women in families.” “The history of chess sets is that they used to just have King, Vizier/General, and other army figures,” Dodson explained. “The queen came onto the board about the same time as the appearance of many powerful queens in England, Russia and Spain.” Dodson reflected on that change and decided that “my set is maternal—I am thinking about family matriarchies, the realm of power in women's lives, how women wield power and the bonds between women in families.” Donna Dodson’s sculptures have been shown in nationally and internationally in solo and group exhibitions, she has received numerous grants, fellowships, and residencies, and her work is in the permanent collections of Provincetown Art Museum, the Art Complex Museum and the Fuller Craft Museum in Massachusetts and the Davistown Museum in Maine. With her husband, the sculptor Andy Moerlein, she is a member of the art collective “The Myth Makers”—but that is a whole other story. Find out more about Donna Dodson at her website at http://donnadodsonartist.blogspot.com/  Comments When I moved the blog from its original site to this site, the comments didn't transfer. Here's what people responded to this post: CYNTHIA KATZ 7/29/2018 03:34:15 am Brilliant! Love all the book resources and the whole concept. ANDY MOERLEIN STUDIO 8/6/2018 04:30:34 am Wow! This sure sums up the huge work Donna has been doing to build a conceptual frame for her sculptures within the architecture of the game of chess. Her focus on women in art and gaming, leadership and competition is brilliant. As we move to a gender neutral (equally gender celebrating) future we need to redefine the oppression within sex roles. Even on the chess board and in the game room. DONNA DODSON 8/10/2018 07:44:45 am Thanks for the shout out Marcia! Much appreciated! Thanks everyone for all the lovely comments too! MARCIA SANTORE 8/12/2018 06:23:51 am Thank YOU, Donna, for the story! And for all your sculptures, which make me so happy.

When Russo arrives at an artist’s studio, he keeps his equipment to a minimum. He works with the same light that the artists have available in their studio spaces. “I think by not bringing in lights, it puts the person more at ease with me. If I spent half an hour setting up lights and running cables it might be more intimidating to them,” he says. There’s also the question of space. “Sometimes I go into spaces and my back is against the wall and I’m tripping over things. People work in little tiny bedrooms. But you figure it out. Every space is really different. Some are great, and with some I’m there scratching my head going, what am I going to do? That’s the hard part of it—lighting is everything in photography. I have to be very creative. All studios have light but usually nothing very sophisticated. Generally speaking, I’d say it’s worked. I’ve never had to go back and reshoot anything.” “The first artist was a gentleman by the name of Domingo Barreres; he was a professor of painting at the MFA Boston. I knew Domingo and took classes with him when I was at the museum school. He’s a very colorful individual. It’s still one of my favorite images in the series,” Russo notes. Originally from Spain, Barreres began teaching at the MFA School in 1967. The photograph (taken in 2012) captures the artist in profile, surrounded by paintings, one elbow on a table awash in cups, brushes, paper, and tubes of paint. It is a timeless portrait of an artist that could have been taken at any point in last 60 years, but for the tip of the Croc clog just visible beside the arm of a chair. For the first couple of years, Russo would reach out to artists he was interested in photographing, and received suggestions from artists as to who else to contact. “In the last couple of years, I don’t solicit artists anymore. A lot of people have been contacting me. And that’s OK, too. I’ve met some amazing people. Most of my friends are artists—not just in Boston but throughout the country—so I can just sit there and talk to people for an hour about their process and what they’re doing, and at the same time I’m looking around and deciding what to do.” But sometimes, he will chase an artist. Elsa Dorfman, for instance. “I chased her for about a year, but Errol Morris was making a documentary about her [The B Side, 2016] and a lot of her time was spent with him. Then out of the blue, she called me and said, ‘Jerry, I can give you an hour.’ I said, ‘I’ll take it!’ I get to her studio in Cambridge and there’s the big Polaroid camera (and who knows who she’s photographed with it!). I put her against the backdrop that she would photograph people on, and she had the remote that she would use to click the shutter on the Polaroid camera. She was awesome. A real child of the 60s, you know? She’s got a big personality—she has this great voice and says what she wants to say. It was great being around her. I set the alarm on my phone for an hour and when it was up, we were done. The next day, they shipped the camera to Teluride for the opening of the documentary. And then she locked the door on the studio and was done. She retired.” Moments like this remind Russo of the historical value of the project, as well. “Somebody said to me, whatever else you’re doing, you’re keeping an archive. That wasn’t my intention when I started, but the more I do it, the more I think of it that way. Given that I graduated from the SMFA, and the connections I made there, I've naturally photographed many faculty and alumni and intend to continue. It's a special place and deserves this type of documentation.” Kim Pashko and David Kelly were fixtures of the Boston art scene, with their huge place in South Boston that served as both their home and their joint studio for more than 25 years. His double-portrait of Pashko and Kelly catches the ambiance of this spacious, cool, arty, much-lived-in, much-worked-in space and freezes it perfectly in time. Shortly after this image was taken, Pashko and Kelly left Boston for Houston, Texas. The Artist Studio Project also raises questions about the effect the economy has on artists, where they can work, and what they can make. “In Boston, with so much gentrification going on in the last couple of decades, it’s hard to find artists spaces anymore,” Russo points out. “And if you can find them, you can’t afford them. When I first moved here in 1996, it was easy to find a studio then. That’s a real problem, now. It’s different for a photographer—if you’ve got a computer, that’s your lab. But if you’re a painter, you need a real studio with ventilation or you have to switch mediums. I’ve been to all sorts of situations with artists and their environments—in their homes, in their attics, in their basements. Some of them live in their studios.” Not every studio requires a well-lit loft or even a room in the basement. Russo heard that filmmaker Roberto Mighty was the first artist-in-residence at the historic 174-acre Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass. Mighty spent a year there preparing his multimedia installation earth.sky, which is based on the cemetery and the stories of people who are buried there. “I called him and said, ‘You have a really interesting studio,’” Russo recalls. “He knew the cemetery like the back of his hand. He’s a filmmaker, so I asked him to choose some locations. We spent the afternoon walking around the cemetery—awesome filmmaker, great guy.” After five years, the end of the Artist Studio Project is in sight. Russo has already photographed well over 100 artists, but still has a few more in mind, which will entail trips to Maine and the Berkshires this summer. “By the end of the year, I hope to start the process of publishing a book of many of these images.”

To see examples of Russo’s different photographic series, visit his website at www.jerryrussophotography.com. Note: All photographs used in this article courtesy of Jerry Russo. So many streams seemed to be flowing together, into one river. “I think it started around 2015,” Carole Groenke recalls. “I’d been going to exhibition committee meetings and discussing themes and where we could have shows.” Groenke, a mixed media artist from Gilford, NH, is an active member of the exhibitions committee for the New Hampshire chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art [full disclosure: that’s where we got to know each other]. She happened to check her calendar and saw that March 22 was designated as World Water Day  Carole Groenke with her piece "Phoenix at the Beach" (right): Mixed-Media found object wall assemblage collaged with newspaper articles, Citra-Solve altered magazine pages, painted glass and mussel shells, hand-made Italian paper, and acrylic and ink on paper. Foam art block print on plexiglass and sculptured, painted, Hydrocal over wood. Left: Halfway to Heaven, mixed media, by Cilla Sheehan. .

Groenke was intrigued. “I’d never heard of World Water Day. I looked it up and came upon The Water Project, a nonprofit organization right there in Concord [New Hampshire] that brings wells and water to South Saharan Africa. I thought I’d check them out and see if they had a place to have an exhibit.” The building, as it turned out, wasn’t really workable for an art exhibition, “but the staff was really excited to talk about what they’re doing and there’s a lot of energy there.” Clean, safe drinking water is scarce. In the developing world, it is the job of women to walk for miles to the nearest river or pond, and bring water back home for their families. But that water is rarely clean enough to drink. According to The Water Project website, “In developing countries, about 80% of illnesses are linked to poor water and sanitation conditions. 1 out of every 5 deaths under the age of 5 worldwide is due to a water-related disease.” The need for clean, safe water affects everything from health, to education, to economic well-being. Groenke and her husband were doing a lot of travelling in 2015, so the exhibition was on the back burner, but every few months, something would bring water issues to her attention. “There was Flint, Michigan, and a couple of other water-related issues that I noticed. I read a lot and I kept discovering more about these water issues. I discovered that World Water Day has been celebrated for years in many countries, but not in the English-speaking countries, for some reason. Just reading about that, I came upon the fact that women in many cultures are trying to get clean water to their families and communities. The theme kept nudging me.” ... it takes very little time for a child to go from slightly dehydrated to a state of shock. If you can’t get safe fluids, you can’t bounce back.” The next October, she read The Water Princess, a children’s book by Susan Verde, illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds. "It’s the story of a model named Georgie Badiel, a former Miss Africa and activist from Burkina Faso, and her childhood dreams of bringing fresh water to her village. The Water Project was working to put in a well in Burkina Faso. It kept coming up.” All these streams were carrying her toward this exhibition, and when she followed them back to their source, Groenke recalled her past as a neonatal intensive care nurse in the 1970s in Cleveland and Tennessee. “I know that if a child is ill, things go south really fast. These water-borne illnesses causing diarrhea and vomiting are very serious. The mortality statistics are very high, because it takes very little time for a child to go from slightly dehydrated to a state of shock. If you can’t get safe fluids, you can’t bounce back.” Groenke began to think more about putting together an art exhibition on the theme of women and water. She was nervous, because she had never organized an exhibition on her own, although she had helped put together many other WCA/NH shows. But the water kept flowing over her consciousness, and it seemed like the right fit for WCA. As Groenke points out, “The national Women’s Caucus for Art is an NGO of the United Nations, and water rights are part of the UN’s Millennium Goals. I liked the idea of using art to make people aware of social concerns. I just feel like this whole thing kept nudging me and I thought I’d better make it come to fruition.” Groenki donated The Water Princess to the New Hampshire Technical Institute library (also in Concord) for their children’s section, and found her venue. She met with Tim Fisher, circulation supervisor, and Stephen Ambra, director, at the NHTI Library. “They were very helpful, let me take pictures and measure everything. They were very accommodating and very excited about it. Whenever I’d come to Concord, I’d go over to NHTI and check in with them to get new questions answered.” The show was scheduled for March 4-29, 2018, to coincide with Women’s History Month and World Water Day. Twenty-five members of WCA/NH are participating [including me]. Groenke says, “We’ve had a wonderful response. It takes a village when you’re putting on a show like this. So many people are helping with everything from tags to fixing website problems. Everyone just worked together so well and it all came together with their help. I couldn’t have done this myself.” In conjunction with the exhibition, Groenke also arranged for a celebration of World Water Day right here in English-speaking New Hampshire with an event at the NHTI Library gallery and speakers Lisa McAllister of The Water Project and Christine Destrempes, an artist who paints about water, at 6 p.m. on March 22, 2018. Her own work has responded to the force of the water concept, as well. “The piece that I did for the show was conceived back in 2015 when I read about the oil spill in Santa Barbara.” That spill reminded her of the 1969 spill in Santa Barbara when Union Oil Platform A blew out. More than 3 million gallons of oil spewed into the ocean, killing over 10,000 seabirds, dolphins, seals, and sea lions. [More full disclosure: my family was living in Santa Barbara at the time, and I remember people taking seabirds home to wash them.] Activists mobilized to create environmental regulation and education, and established Earth Day (first celebrated in 1970, and now an annual event on April 22) in response to this event. Groenke started a mixed media piece. “I was experimenting with hydrocal at that time. It’s like plaster of Paris but faster. In 20 minutes it can go from a drippy consistency to like sour cream to like cement that you can spread around with a night. I’d get together with my friend Cilla Sheehan to play with it. One time, I was experimenting by using it on chunks of pine. Four of the five pieces I did that day went into the piece that’s in this show.”

Recently, I met a college student at an opening of one of my solo exhibitions and had a fascinating conversation with him. I didn’t find out his name but I hope I get the chance to sometime. He looked closely and carefully. He asked great questions. He stuck with the paintings that interested him for a long time and noticed more and more and more. This is the viewer I paint for. I asked him about himself and he told me that he was student at the university, studying business but thinking of switching to finance. He had never taken an art history course, he didn’t make art of his own—he was just fascinated. I suggested that he take the opportunity to learn more about art and to see as much art as he could. I told him that the art world needs viewers like him. Afterwards, of course, I thought of other things that I wish I had said to him. So I’m going to say them here: Unknown student, one day you are going to be a remarkable art collector. You may not have disposable income yet, but you are going into a field where having disposable income is likely. I hope you spend it on art you love. Because there are two kinds of art collectors. There is the kind that buys for investment. Generally, collectors in this group are not interested in the art as art; they are interest in art as a commodity. They buy what Larry Gogosian or someone like him tells them will increase in value, and then they store it in an offshore freeport where it doesn’t see the light of day until it is sold for a profit. Then there is the other kind of art collector; the kind you will be. This is the person who collects art to live with. The person who buys the work that speaks to them, and looks at it, and learns from it, and grows as a human being because of it. This is the person who collects based on the artwork itself, not the name of the artist. Sometimes this collector will purchase something by a famous artist (living or dead) and sometimes this collector will purchase something from someone unknown, or almost unknown, because the work speaks to them. This is the kind of collector that artists value because this collector is the person they need to bring about the final completion of the work. Making art is an act of communication. That means it requires both a sender and a receiver. If an artist makes a painting or a sculpture or a piece of music or a dance, and nobody ever apprehends it, the work is not finished. This kind of collector—the kind you will be one day—is that receiver. Whether you collect that piece or not, whether you encounter it in a gallery or a museum or an artist’s studio or a friend’s home or wherever, when you give it your careful attention, then the piece has the chance to do its work. The act of communication is complete. I had another interaction that day that left me wishing I had said something different. As my family and I were getting ready to leave the building after the opening, we passed a man who had gone through the gallery on his way to another event that was going on in the same building. He had asked us where to find the room where the event was being held, so we knew he wasn't part of the faculty or staff. When we saw him again, he turned around and angrily asked me what the point was of showing art in the university gallery. “Nobody is going to see it! Who is going to buy it? Students?” he said. It seemed like this question had been on his mind and he was grabbing the opportunity to ask. I gave him some sort of answer, but not a great one, because I was taken by surprise. I could have explained at length about universities having a cultural mission to the community, and that there is more to looking at art than commerce. I could have said a lot of things. But his question answered itself: Angry stranger, you saw it. Comments

When I moved the blog from its original site to this site, the comments didn't transfer. Here's what people responded to this post: KAREN FRIEDLAND 11/3/2017 06:28:07 pm Hi Marcia- Good story! Loved the last line. It occurred to me that there was a likelihood that your student signed up for your mailing list that day. Perhaps you could link to this post in one of your newsletters. Your young man might show up-you never know! It's a fun mystery.😄 best, Karen \JESSICA SALINAS 11/4/2017 07:06:36 am Re the Angry Stranger: This person is a thwarted artist himself. Sometimes being awful to others is how we try to tell ourselves something we need to know. REPLY MARCIA SANTORE 11/5/2017 08:42:15 am I like that idea better than my assumption that he was mad at himself for being late and lost to his event and wanted to take it out on someone else, preferably female and preferably a stranger. [email protected] 11/4/2017 04:21:25 pm I like this. Keep reaching out to the universe. The world of art is changing, and yes, changing the world. The language of NEXT is pictorial. That said, words matter being seminal ideas (logos). Please sign me up - and do let me know as well if you'd like to hear more from "rozolution" - best, BETH BLANKENSHIP 11/4/2017 08:03:00 pm I saw your announcement on the Creative Capital Alumni Facebook page and clicked on the link—boy, am I glad I did. Thank you so much for your thoughtful writing, it was a pleasure to read this blog post and I look forward to reading more. MARY ANN MCGARRY 11/6/2017 02:34:54 am Reading your description of the first business student artist reminded me to communicate with artists when I have the chance. I want to let them know which pieces speak to me and how and why. REPLY MARCIA SANTORE 11/6/2017 03:58:36 am I agree with you completely, Mary Ann. That means a lot to the artist and provides a deeper understanding of the work for the viewer, even if their opinions differ. |

AuthorI'm Marcia Santore, an artist and writer. artYOP! is a blog about artists and their stories, including mine. The artYOP! blog is currently on hiatus. Archives

April 2019

Categories |

- Home

- About

-

Portfolios

- Small Works & Artwork Under $150

- Digital Work

- Infinite Possibility >

- Figures in Motion >

-

Dance of ...

>

- Dance of Alignment

- Dance of Apprehension

- Dance of Benevolence

- Dance of Compassion

- Dance of Courage

- Dance of Curiosity

- Dance of Delight

- Dance of Delirium

- Dance of Discernment

- Dance of Discretion

- Dance of Disquiet

- Dance of Euphoria

- Dance of Gratitude

- Dance of Impatience

- Dance of Incredulity

- Dance of Indecision

- Dance of Patience

- Dance of Rejuvenation

- Dance of Tranquility

- Inexteriors >

- Ichthyoforms >

- Composite Rhythms: Works on Paper >

- Art in Place

- Other Projects

- News

- Own Art

- Contact

- artyopblog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed