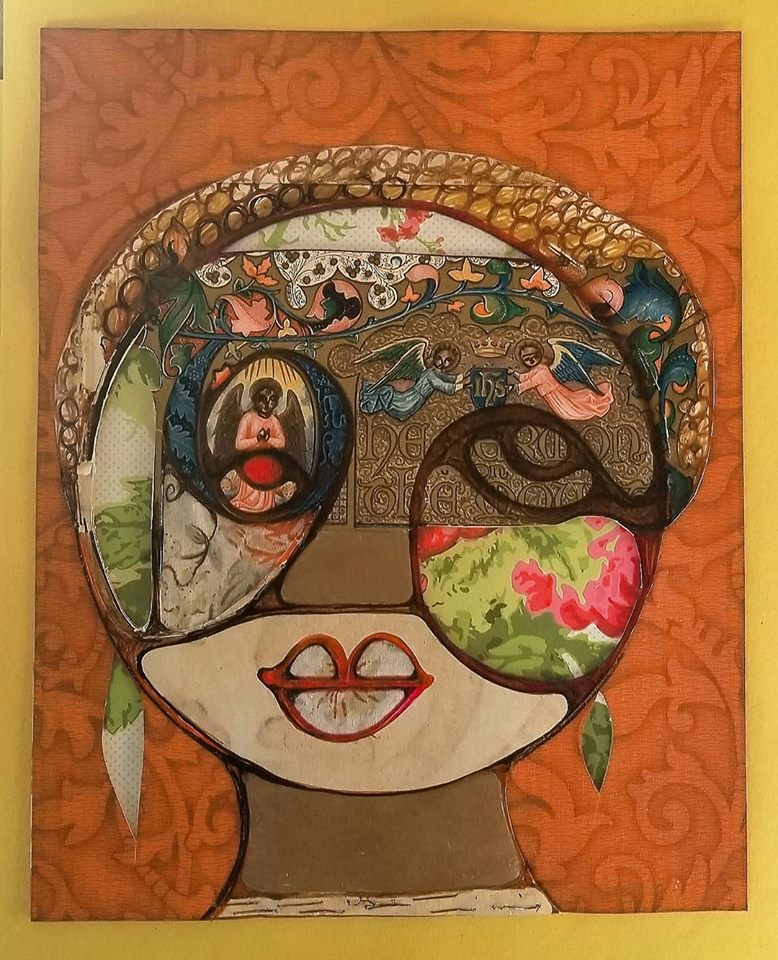

“My work has always been colorful, bright—the main subject matter has always been women, children, and family with a spiritual twist,” Kedem-DuBose says. She found it hard to create during the early years of her depression, as she had no desire to produce negative imagery. Seeking a way to take her mind off all the loss surrounding the divorce, including the absence of her youngest child, she decided to enroll in the interior design program at Harrington College of Design. She received two scholarships, one based on her art portfolio, and one as a Service and Leadership Scholar. While a student, she was invited to speak on a panel of professional Black artists, and was included on the Dean's List. “These accomplishments helped me to see that I hadn’t lost anything creatively, and also helped me to get through some of the most challenging aspects of the divorce,” she recalls. “My work became more technical, and I started to work more with the elements of design instead of the visual art foundation with which I was most familiar.” Going back to school revealed another issue that had gone unrecognized previously. “I’d forget from one week to the next what was due, so there were times when I worked for days without sleep to complete a project that I had weeks to complete.” Finally, a professor took her aside and said, “Makeba, we think you’re brilliant here, very talented, but have you ever considered being tested for ADD?” She knew he was on to something, and was subsequently tested and diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. Knowing this was helpful and she tried ADD medications, but it turned out her body did not react consistently well to them, so she learned to manage on and off with them over the years. In 2014, she met urologist Dr. Adam Murphy, cofounder of the Chicago Global Health Alliance, and began working with CGHA, first as curator of the non-profit's Annual Art for Global Health Fundraiser, then as creative director. She has been coordinating art auctions that help fund the organization’s work in the United States and Liberia ever since. She went with Dr. Murphy to call on a gallery owner she knew well, only to find her old friend in precarious health. Despite her own health problems, and being newly divorced, Kedem-DuBose began helping her friend by offering transportation, shopping, cooking and cleaning, and by consolidating the art in the gallery and selling it off. It was at this point—with practically no money and deep in depression—that Kedem-DuBose discovered what would become the first step on her journey back. She found a cache of old artist catalogs in the gallery files and felt inspired to make art out of the paper. She deconstructed the catalogs, dyed the paper pages in vats, drew on them, painted on them, put them together with pins, staples, grommets—the only things she had. The first pages were dark blue—reflections of her own “blues” as she poured all of her depression into the work over several years. Then something new started to happen. Purples. She calls purple “my best of blue—I always felt connected to the color purple, from Catholicism to Voodoo to Judaism—there’s a lot of stuff in there. Purple was spiritual and less depressing.” So the blue morphed into purple, and then she noticed that she was adding bits of a new color—red. And with red, Kedem-DuBose says, “I refound my warrior spirit.” In November 2017, the complete work, called “The Best of Blue: A Work in Progress” was displayed at Adler University’s Chicago campus. The mosaic of pages snake up and down along the wall, like the emotional ups and downs of the previous eight years. “Best of Blue was very therapeutic for me,” she says. “I was working out a lot of that stuff through art—even though I still have challenges. Some of the paintings I started back then, I’m just going back to now. My best work comes out of my depression. I’ve never been one to shy away from any subject. I’m as comfortable talking to a White person about race as a Black person. I’m the same way with my work. Sometimes I can’t restrain myself, but my intentions are always good—not just for me or for Black people, but for everyone.” Her newest work continues her interest in religious imagery, bright color, and inclusiveness, but with added layers and textures. She alters pages from old books to include people of color and women. “Sermon” is a newer work that includes the text of the Sermon on the Mount and angels repainted with African faces. “I don’t want to exclude anyone—my work is very rainbow like,” says Kedem-DuBose, “but being African American, the faces I create will always have something African about them.” She is also exploring the connections between religions, especially the Catholicism she was raised in and Ifá, which is practiced throughout the African diaspora and influences religious practices such as Vodou and Santería. “Ifá was brought to America through the slave trade,” Kedem-DuBose explains. “My enslaved African ancestors incorporated it into Catholicism. There are a lot of similarities in all religions—we’re all connected. We’d be better off to recognize that. All the major religions say the same thing. Every religion has love, but love has no religion. My religion is love. It’s a very radical viewpoint--in a world filled with ugliness, but there is still beauty.” To learn more about Makeba Kedem-DuBose, start with her Facebook page. Comments

When I moved the blog from its original site to this site, the comments didn't transfer. Here's what people responded to this post: KIMBERLY J B SMITH 3/2/2019 06:11:49 am Great journey story, enjoyed the Best of Blue as it appeared like waves across the wall. Always like to hear what is going on in Chicago! Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI'm Marcia Santore, an artist and writer. artYOP! is a blog about artists and their stories, including mine. The artYOP! blog is currently on hiatus. Archives

April 2019

Categories |

- Home

- About

-

Portfolios

- Small Works & Artwork Under $150

- Digital Work

- Infinite Possibility >

- Figures in Motion >

-

Dance of ...

>

- Dance of Alignment

- Dance of Apprehension

- Dance of Benevolence

- Dance of Compassion

- Dance of Courage

- Dance of Curiosity

- Dance of Delight

- Dance of Delirium

- Dance of Discernment

- Dance of Discretion

- Dance of Disquiet

- Dance of Euphoria

- Dance of Gratitude

- Dance of Impatience

- Dance of Incredulity

- Dance of Indecision

- Dance of Patience

- Dance of Rejuvenation

- Dance of Tranquility

- Inexteriors >

- Ichthyoforms >

- Composite Rhythms: Works on Paper >

- Art in Place

- Other Projects

- News

- Own Art

- Contact

- artyopblog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed